MIGHTY NINETY

Chapter 10: The Storm

Author's note: Most photographs published in books and other sources said to show ships caught in the Typhoon of December 1944 were not taken during this storm. Most were taken in the South China Sea in January 1945.

This section on the Typhoon of December 1944 (re-named Typhoon Cobra in the 1950s) will only include photographs that can be confirmed associated with the December 1944 storm. The fact that so few images exist illustrates the intensity of the storm.

Waves break over the bow of an oiler from Task Group 30.8 as refueling attempts begin in the late morning of 17 December 1944. The weather progressively worsened throughout the day.

-U.S.Navy photo in NARA collection 80-G

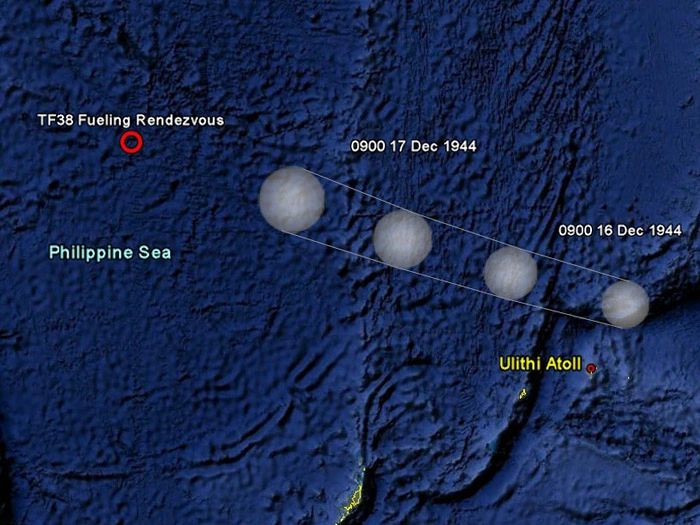

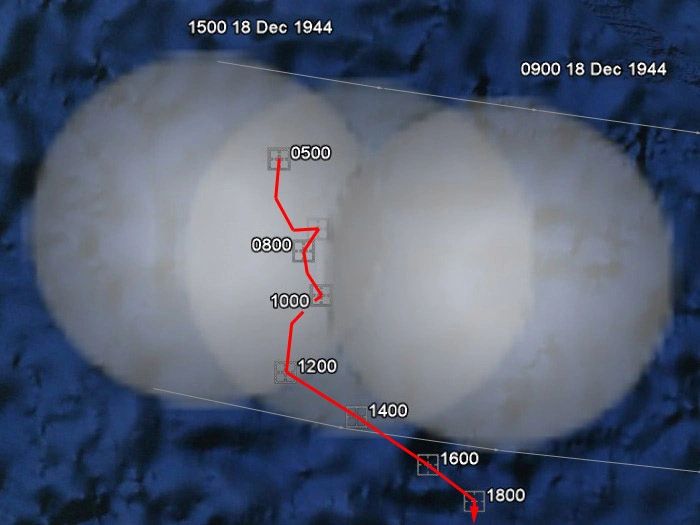

This track chart depicts the collision course of USS Astoria and Third Fleet attempting to refuel while the typhoon closes in on 17 December 1944.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

16 December 1944

Late in the afternoon, Task Force 38 broke off from the Philippines and began the 400 mile trip east to rendezvous with their logistics support group, Task Group 30.8. The rendezvous point was beyond the range of Japanese fighters, yet allowed for the quickest possible return to coverage of Luzon airfields.

Although it would only later become clear, this underway replenishment placed the fleet directly in the path of a growing pacific storm. The storm, the first to be christened by the U.S. Navy Aerological Division, was later referred to as Typhoon Cobra.

The storm was first recorded as a "tropical disturbance" estimated to be moving north-northwest on a course that would take it hundreds of miles from the fleet. This error was to be the first of many in identifying the track of the storm.

Author's note: Most photographs published in books and other sources said to show ships caught in the Typhoon of December 1944 were not taken during this storm. Most were taken in the South China Sea in January 1945.

This section on the Typhoon of December 1944 (re-named Typhoon Cobra in the 1950s) will only include photographs that can be confirmed associated with the December 1944 storm. The fact that so few images exist illustrates the intensity of the storm.

Waves break over the bow of an oiler from Task Group 30.8 as refueling attempts begin in the late morning of 17 December 1944. The weather progressively worsened throughout the day.

-U.S.Navy photo in NARA collection 80-G

This track chart depicts the collision course of USS Astoria and Third Fleet attempting to refuel while the typhoon closes in on 17 December 1944.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

16 December 1944

Late in the afternoon, Task Force 38 broke off from the Philippines and began the 400 mile trip east to rendezvous with their logistics support group, Task Group 30.8. The rendezvous point was beyond the range of Japanese fighters, yet allowed for the quickest possible return to coverage of Luzon airfields.

Although it would only later become clear, this underway replenishment placed the fleet directly in the path of a growing pacific storm. The storm, the first to be christened by the U.S. Navy Aerological Division, was later referred to as Typhoon Cobra.

The storm was first recorded as a "tropical disturbance" estimated to be moving north-northwest on a course that would take it hundreds of miles from the fleet. This error was to be the first of many in identifying the track of the storm.

17 December 1944

0800

Fueling was difficult from the very start as wind and seas began to pick up. USS Astoria sailor Deno Dolci recalled that "we had a hell of a time getting the lines over, the waves were so high. All hands were called up to carry supplies.

1200

Conditions worsened throughout the morning as ships attempted to refuel. In one incident, destroyer Maddox had a fuel line break, almost causing a collision with her oiler Manatee. Escort carrier Kwajalein, attempting to transfer replacement planes and pilots to the fast carriers, canceled all air operations and personnel transfers. Her crew focused instead on lashing planes to the deck with steel cables and deflating their tires. As the day progressed, the practice of securing aircraft was adopted by carriers throughout the fleet.

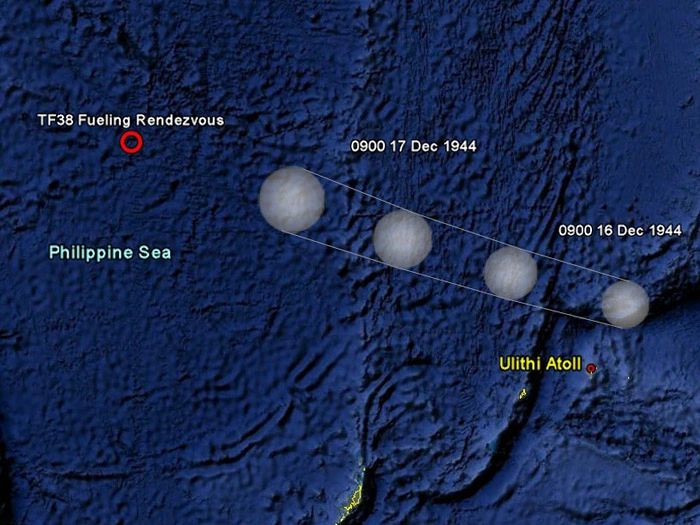

At 1251 Admiral Halsey ordered all ships to cancel fueling attempts for the day and steam northwest; a second fueling rendezvous would be attempted the next morning at 0600. Halsey made this decision based on the conclusion that the storm was moving away to the north. This new location would keep the fleet close to Luzon yet out of enemy fighter range, allowing the fast carriers to get back into action on schedule. In reality, the storm was 300 miles closer than realized and bearing down on the fleet.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

1500

The sea had become too rough for aircraft recovery. The last two planes returning from Combat Air Patrol were ordered to ditch in the ocean. Their pilots bailed out and were recovered by a destroyer.

Skippers across the fleet shared opinions and predictions. It became consensus that the new refueling point lay in the path of the storm, a notion that was closer to the mark but still not accurate.

0800

Fueling was difficult from the very start as wind and seas began to pick up. USS Astoria sailor Deno Dolci recalled that "we had a hell of a time getting the lines over, the waves were so high. All hands were called up to carry supplies.

1200

Conditions worsened throughout the morning as ships attempted to refuel. In one incident, destroyer Maddox had a fuel line break, almost causing a collision with her oiler Manatee. Escort carrier Kwajalein, attempting to transfer replacement planes and pilots to the fast carriers, canceled all air operations and personnel transfers. Her crew focused instead on lashing planes to the deck with steel cables and deflating their tires. As the day progressed, the practice of securing aircraft was adopted by carriers throughout the fleet.

At 1251 Admiral Halsey ordered all ships to cancel fueling attempts for the day and steam northwest; a second fueling rendezvous would be attempted the next morning at 0600. Halsey made this decision based on the conclusion that the storm was moving away to the north. This new location would keep the fleet close to Luzon yet out of enemy fighter range, allowing the fast carriers to get back into action on schedule. In reality, the storm was 300 miles closer than realized and bearing down on the fleet.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

1500

The sea had become too rough for aircraft recovery. The last two planes returning from Combat Air Patrol were ordered to ditch in the ocean. Their pilots bailed out and were recovered by a destroyer.

Skippers across the fleet shared opinions and predictions. It became consensus that the new refueling point lay in the path of the storm, a notion that was closer to the mark but still not accurate.

At 1533 Halsey waved off the second rendezvous point and designated a third one, much farther to the south. He directed the fleet to a new heading of due west, 270 degrees. The fleet began to outpace the weather and conditions improved somewhat, but when they turned south at 0000 on 18 December the storm began to gain on them again.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

18 December 1944

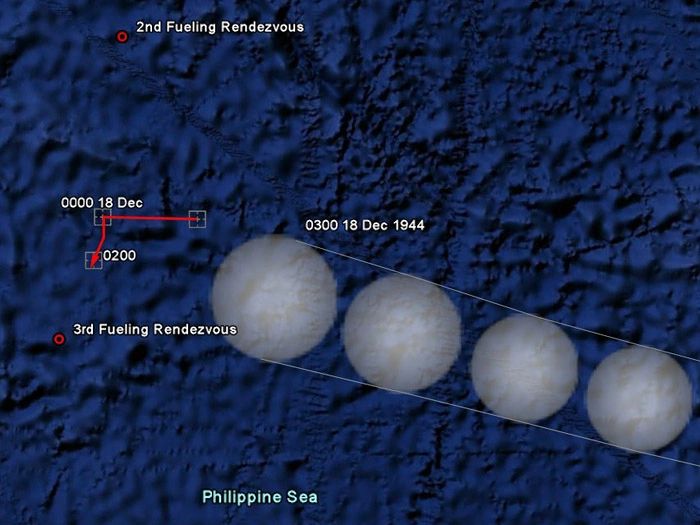

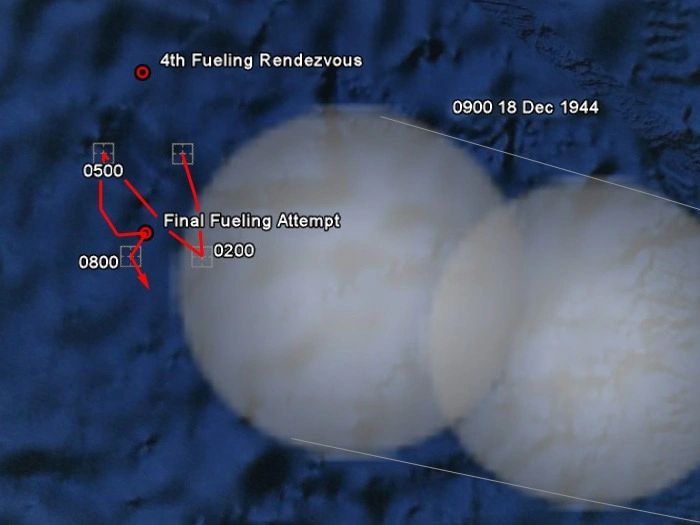

By 0200 Halsey realized that his ships would not be able to reach the third rendezvous, so late in the evening he changed the location of the fueling rendezvous yet again. This fourth location was believed to provide more favorable weather while still maintaining a safe distance from Japanese airfields. Unfortunately, this decision pulled the fleet directly back into the path of the advancing storm.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

0500

Conditions grew worse overnight. Shortly after 0500 the fourth fueling rendezvous was called off completely and all ships were ordered to head due south to escape the storm. Several destroyers were at critically low fuel levels; they made attempts to refuel that proved dangerous and futile.

0800

Spread out over many miles of ocean, the ships of Third Fleet had very different experiences. In Astoria's task group weather conditions weren't severe beyond heavy seas; Hancock recorded only "scattered showers" until "heavy continuous rain" began at 0800.

For ships nearest to the storm, conditions were so bad that two escort carriers requested permission to break formation and fend for themselves. From Morison's Liberation of the Philippines:

Salt water was blowing horizontally at bridge level. There seemed to be no separation between sea and sky. The sound of the wind in the rigging, especially in the large "bedspring" radar, was frightening.

0900

The storm began to consume the fleet. The light carrier USS Independence reported a man overboard; another followed within minutes. Aircraft broke loose from their cables on the hangar deck of USS Monterey and exploded into flames. The crew of the Monterey spent the next hour working to bring fires under control as the ship slowed and lost steerage.

Above: In one of the very few photographs taken during the December typhoon, USS Langley CVL-27 rolls through 30 degrees to starboard on the morning of 18 December 1944.

Below: In an uncropped version of the same image, battleship Washington BB-56 maintains an even keel as Langley rolls, showing the relative stability of ships caught in the storm.

-U.S. Naval History and Heritage Center photo

By 1000 the fleet was in the heart of the storm. Barometer readings fell rapidly and the wind began backing counterclockwise, tell-tale signs of a typhoon. Ships maneuvered independently for the next eight hours as each fought its own battle.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

USS Wisconsin radioed that one of her Kingfisher floatplanes had been torn from her deck. A few minutes later cruisers Boston and Miami also reported planes overboard. USS Cowpens became the second light carrier to report hangar deck fires from unsecured aircraft.

From the Mighty Ninety cruise book:

It was pretty rough that morning and the waves were higher than the bridge, but it was so novel that we didn’t realize the danger until it was all over.

1200

At 1228 an escort carrier reported fires--Cape Esperance. Her planes had broken loose on the flight deck, flames were rising to the height of the bridge, and the ship was in serious jeopardy of being lost. USS Miami was ordered to stand by Cape Esperance. Fortunately wind and sea extinguished the fires, clearing burning aircraft from her flight deck and reducing her topside weight. Cape Esperance was saved by the same storm that damaged her.

From Morison's Liberation of the Philippines:

[By afternoon] every ship was laboring heavily; hardly any two were in visual contact; many lay dead, rolling in the trough of the sea... Sailors peered out on such a scene as they had never witnessed before, and hoped to never see again. The weather was so thick and dirty that sea and sky seemed fused in one aqueous element.

1800

By early evening the worst of the storm had passed. Third Fleet was scattered over an area of 3000 square miles of ocean. Although several ships had already been directed back to Ultihi for repair, the overall state of the fleet had yet to be ascertained. At 1848 Halsey ordered a search to begin for men overboard.

From Calhoun's Typhoon: the Other Enemy:

As the 18th of December passed into history, the Commander Third Fleet could not possibly have had any real appreciation of the magnitude of the disaster that had just befallen his ships. Not until the 19th did the tragic picture begin to unfold.

At 1228 an escort carrier reported fires--Cape Esperance. Her planes had broken loose on the flight deck, flames were rising to the height of the bridge, and the ship was in serious jeopardy of being lost. USS Miami was ordered to stand by Cape Esperance. Fortunately wind and sea extinguished the fires, clearing burning aircraft from her flight deck and reducing her topside weight. Cape Esperance was saved by the same storm that damaged her.

From Morison's Liberation of the Philippines:

[By afternoon] every ship was laboring heavily; hardly any two were in visual contact; many lay dead, rolling in the trough of the sea... Sailors peered out on such a scene as they had never witnessed before, and hoped to never see again. The weather was so thick and dirty that sea and sky seemed fused in one aqueous element.

1800

By early evening the worst of the storm had passed. Third Fleet was scattered over an area of 3000 square miles of ocean. Although several ships had already been directed back to Ultihi for repair, the overall state of the fleet had yet to be ascertained. At 1848 Halsey ordered a search to begin for men overboard.

From Calhoun's Typhoon: the Other Enemy:

As the 18th of December passed into history, the Commander Third Fleet could not possibly have had any real appreciation of the magnitude of the disaster that had just befallen his ships. Not until the 19th did the tragic picture begin to unfold.

19 December 1944

Sometime after midnight, destroyer escort USS Tabberer DE-418 conveyed a message to Halsey via another ship stating:

"Now engaged in picking up survivors of Hull DD-350... Hull capsized with little warning at about 1030. Only two life rafts launched and neither yet sighted... Have ten enlisted survivors and will remain in area searching until after daylight or until otherwise directed."

Tabberer went on to report her own damage. Her foremast had been torn down by gale winds during the storm. Radar and radio gone, she was operating on emergency equipment and barely managed to convey her message to a nearby ship.

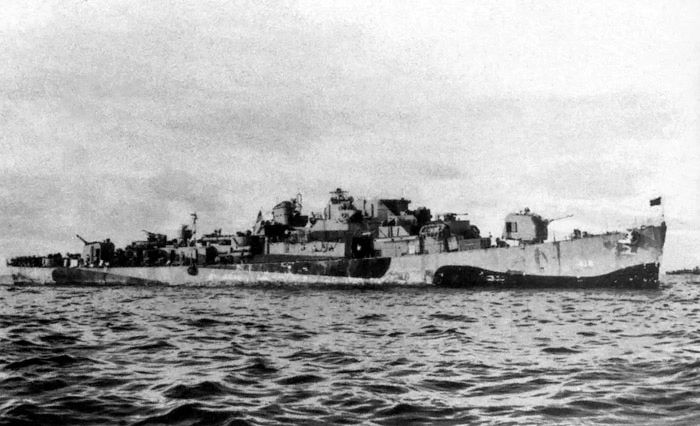

USS Tabberer DE-418 as she looked following the Typhoon of December 1944.

-U.S. Navy photo reproduced from Halsey's Typhoon, Drury and Clavin

As reports came in through the night, several destroyers were unaccounted for. Tabberer stayed on station working a box search pattern despite her damage. In the hours that followed she pulled 28 more USS Hull sailors from the water.

Seas remained heavy, but ships could finally fuel. Although three DDs were missing and three CVLs were detached back to Ulithi for repairs, Halsey and McCain were mindful of their obligation to return to Luzon for precious air cover. Lives hung in the balance both in the surrounding waters and back at Mindoro, but getting back into the fight was top priority.

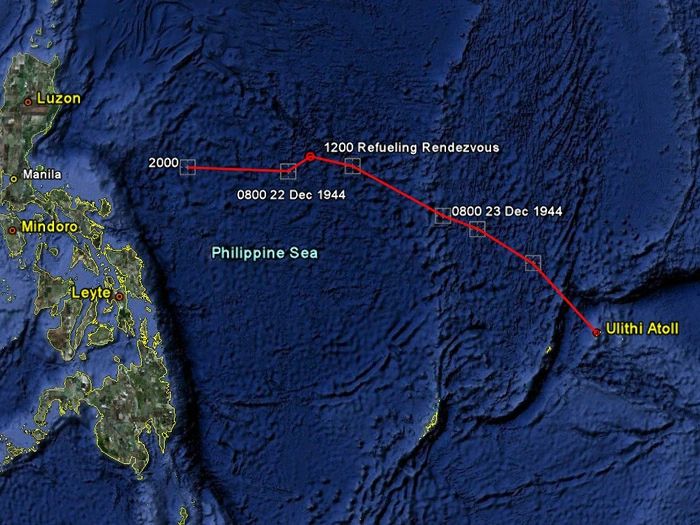

The track chart of Astoria as the combined fleet fought its way clear of the storm. In their wake, the fleet learned of the lost destroyer USS Hull.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

Although USS Astoria had weathered the storm, her Kingfisher floatplanes had not. As the ship refueled and readied to return to the Philippines, crew members assessed damage on the fantail.

Under clearing skies, Astoria sailors begin work on the starboard OS2N-1 Kingfisher. The plane's port wing and centerline pontoon are badly damaged. Note the M-1926 life belt on the man at left.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

The underside of Astoria's starboard OS2N-1 Kingfisher. Like all ships equipped with Kingfishers, Astoria's planes could not be stored in her hangar due to non-folding wings. They had to be lashed to their catapults, resulting in losses throughout the fleet.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

A third photo from 19 December 1944 clearly shows the extent of damage to the plane's port wing. Note the sailor at right wearing foul weather gear.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

A final view of the damaged starboard-side plane. After it was untied and righted, the ruined Kingfisher was discarded overboard.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Above and below: Several light carriers were badly damaged. Shown is the burned-out hangar deck of USS Monterey CVL-26, where future American President LT Gerald Ford led efforts to fight fires at the height of the storm.

-U.S. Navy photos in NARA Record Group 80-G

20 December 1944

With fueling operations completed, the battered and reassembled Fast Carrier Task Force began its return to the Philippines. Halsey had promised MacArthur that his ships would be back on station to resume air strikes the next day. Halsey hoped to now employ the storm to his advantage, advancing behind it to mask the approach of his ships.

The track chart of Astoria as the fleet steamed north on 19-20 December 1944. Their path brought them into position to detach the Logistic Support Group in the search for survivors while the Fast Carrier Task Force used the storm to mask a return approach to Luzon.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

In the early morning of 20 December, Halsey received a report that carried with it more devastating news. Overnight one of the destroyer escorts engaged in the search for survivors had recovered five men from a second lost ship, USS Spence. Like Hull, Spence had rolled and taken water. But unlike Hull, Spence was not an obsolescent four-stack ship; she was a modern Fletcher-class destroyer from Astoria's task group. The survivors reported the sinking happened so quickly that it was unlikely that many men survived.

The typhoon continued to thwart Admiral Halsey's plans. As the fleet closed in on the Philippines, it began to overtake the now-slowing storm. The storm stalled over Luzon, rendering it impossible to resume air operations.

21 December 1944

Overnight Halsey radioed to MacArthur: "Regret unable to strike on 21st due to impossible sea conditions. Am retiring eastward." With that statement, fast carrier support of Operation LOVE III ended. Task Force 38 turned back south for one last search for survivors. A third ship--USS Monaghan--remained unaccounted for.

The fleet moves back into the storm track on 21 December 1944. Many ships, including USS Astoria, sighted debris in the water as the search for survivors continued. On the morning of the 21st, a handful of survivors of USS Monaghan and more men from Hull were rescued after three full days in the water.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

Combat air patrol over Task Group 38.2 on 21 December 1944. The task force was finally far enough from the stalled storm to launch planes.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

22 December 1944

An F6F from USS Independence performs CAP over Task Group 38.2 in the morning hours of 22 December 1944. Note the radar pod on the starboard wing used for night operations. This photograph was taken from Hancock CV-19. Miami CL-89 is at left.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA Record Group 80-G-259055

Sailors watch from the fantail of oiler USS Mascoma AO-83 as Astoria fuels to her port side on 22 December. In the distance, USS Hancock rides heavy seas as destroyers come alongside for fueling.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Following a fueling rendezvous, the search for survivors was called off at sundown on 22 December. 93 men had been pulled from the water over the course of four days. As the Fast Carrier Task Force steamed for the safe confines of Ulithi, they learned of the confirmed loss of the third missing destroyer, USS Monaghan. Many other ships had suffered significant damage, and hundreds of sailors were known lost at sea.

-manipulated from Google Imagery

Heavy seas continued in the wake of the typhoon days later. In this image from 23 December 1944, her last full day at sea before arriving at anchorage, the bow of USS Astoria plunges into the water

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Continue to CHAPTER 11: Home for the Holidays

CLICK ON PHOTOS TO ADVANCE TO NEXT CHAPTER

BACK TO SHIP HISTORY

Sources:

Blodgett, Herbert. "Remembering Typhoon Cobra." U.S. Navy Cruiser Sailors Association Quarterly, Summer 2006, pp. 29-30.

Calhoun, C. Raymond. Typhoon: The Other Enemy.

Melton, Jr.,Buckner F. Sea Cobra.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of

Peddie, Jim. Private collection of ASTORIA CL-90 documents.

Schnipper, Herman. Excerpt from “Typhoon Cobra: December 18, 1944.” The Jerseyman, December 2003, p.10

Schnipper, Herman. Private photo collection.

USS MIAMI CL-89 cruise book. 1946.

www.navsource.org cruiser photo archive.