MIGHTY NINETY

Chapter 13: OPERATION GRATITUDE

Task Force 38 raids Japanese shipping in the South China Sea

Task Group 38.2 refuels in the South China Sea on 11 January 1945. USS THE SULLIVANS DD-537 and ASTORIA are taking on fuel underway from opposite sides TALUGA AO-62. Note the shamrock on THE SULLIVANS' forward stack. Halsey's flagship NEW JERSEY BB-62 is in the background at left.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Following the surface actions of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, Admiral Halsey was champing at the bit for an opportunity to finish off ships of the Japanese Combined Fleet. Intelligence suggested that the remaining capital ships that had survived the actions at Leyte Gulf were divided into two sections--one group in the Inland Sea of Japan and the other in the South China Sea. Having missed the opportunity at Leyte, Halsey desperately wanted to engage the remaining Japanese surface threat and finish it off.

In January 1945, logistical requirements of the Luzon invasion made this desire a practical reality. The possibility of Japanese warships in the South China Sea posed a significant threat to the supply lines for Luzon. Airfields along the coast of French Indochina (modern Vietnam) and China were also within striking distance of these supply lines. The timing was ideal for a Task Force 38 incursion into Japanese-controlled waters, both to hunt for surface vessels and to strike other targets of opportunity.

9-10 January 1945

Overnight the ships of the Fast Carrier Task Force made a high-speed run southwest, entering the South China Sea via the Bashi Channel of Luzon Strait. This was the first time since the earliest days of the war that U.S. surface vessels had entered these waters.

At 0500 Air Emergency Stations were called--three Japanese "snoopers" had been picked up on radar. The night CAP fighters from USS INDEPENDENCE intercepted them to engage before they could report the presence of the task force.

11 January 1945

Poor weather conditions had prevented fueling the day before, but the morning of the 11th proved successful. Fueling and supply was complete by noon, and effective CAP ensured that the fleet was not discovered while at their most vulnerable. Mail and fuel oil weren't the only things circulating; scuttlebutt began to fly about what the next day might bring.

Confirmation came soon enough. The target area was Cam Ranh Bay, where capital ships of the Japanese Combined Fleet were believed to be anchored. USS ASTORIA's Task Group 38.2, fortified by cruisers and destroyers from TG38.1, was given the assignment of entering Cam Ranh Bay to bombard the area and destroy these surface vessels.

Following fueling, USS BALTIMORE and BOSTON plus five destroyers joined Task Group 38.2. At 1400 this fortified task group, including the night carriers, detached from the main force and began its run-in toward Cam Ranh Bay.

Admiral Halsey sent a message to his ships:

You know what to do--give them hell--God bless you all. HALSEY.

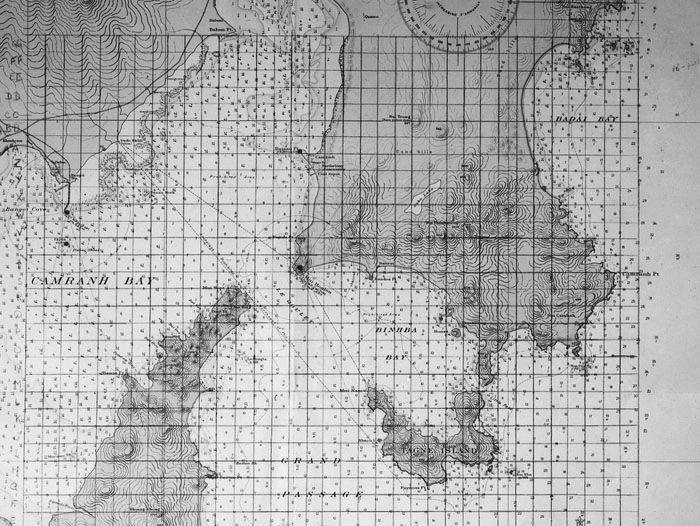

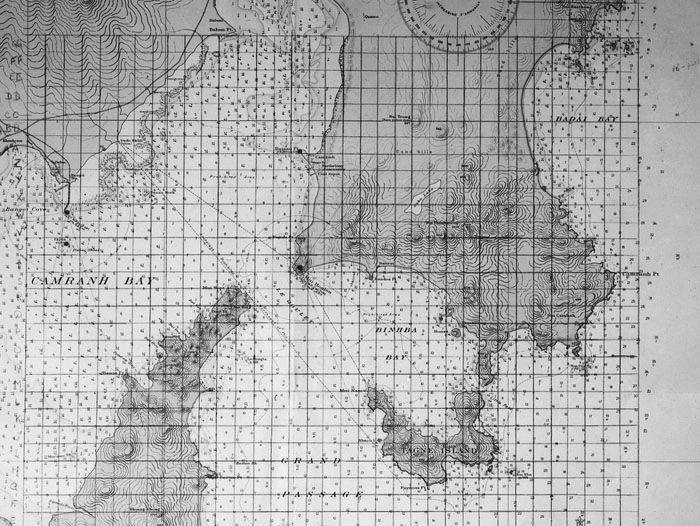

The grid chart used by USS ASTORIA CL-90 in preparation for the Cam Ranh Bay fire mission. The ship was to fire over Tagne Island (lower right) into the bay while her floatplanes spotted her fire.

-courtesy of Herman Schnipper

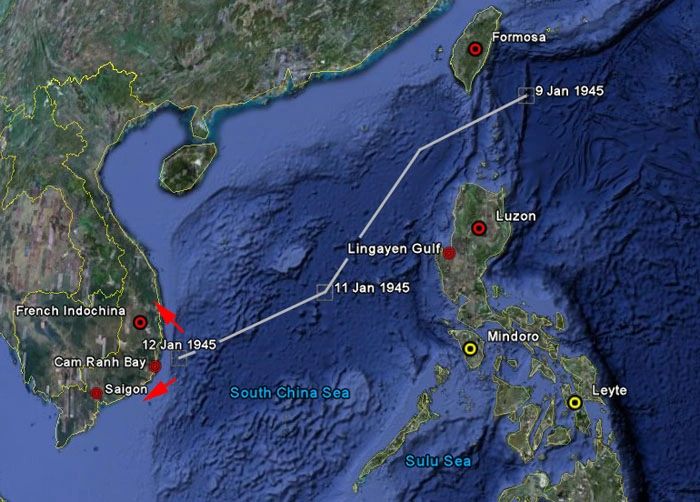

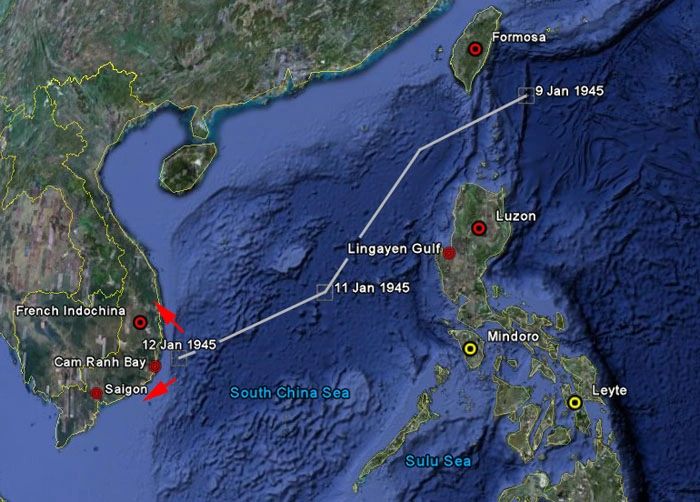

Track chart of USS ASTORIA as Task Force 38 moves through Bashi Channel between Luzon and Formosa into the South China Sea. After refueling on 11 January, the fortified Task Group 38.2 moved in toward Cam Ranh Bay. The arrows indicate air strikes conducted against Saigon, Cam Ranh, and the coast of French Indochina.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

12 January 1945

At 0300 the night carriers took the lead in the attack on Cam Ranh Bay. Eight two-plane search teams of TBM Avenger bombers launched from ENTERPRISE and INDEPENDENCE.

From Edward Stafford's The Big E:

The blacked-out TBMs fanned out over the [Indochina] coast from a hundred miles to seaward like the fingers of an exploring hand, peering through the night with radar, laying naked suspicious areas with the harsh brilliance of parachute flares, occasionally scorching a rocket or two into likely targets. And behind the probing fingers, the heavy fist of the day carriers was cocked and ready.

At 0731, as the surface strike unit approached Cam Ranh, aircraft were launched from carriers across all task groups. The Avengers launched from the night carriers had provided precise information on locations of Japanese targets, and strikes were dispatched accordingly.

No heavy ships had been sighted. The Japanese Combined Fleet was not in Cam Ranh Bay, nor anywhere else that had been scouted. Frustrated, Halsey ordered the surface strike unit to turn back and the task groups were reconstituted. The focus for the day turned to making the most of the aerial raids taking place against smaller Japanese surface vessels, merchant shipping, and port facilities.

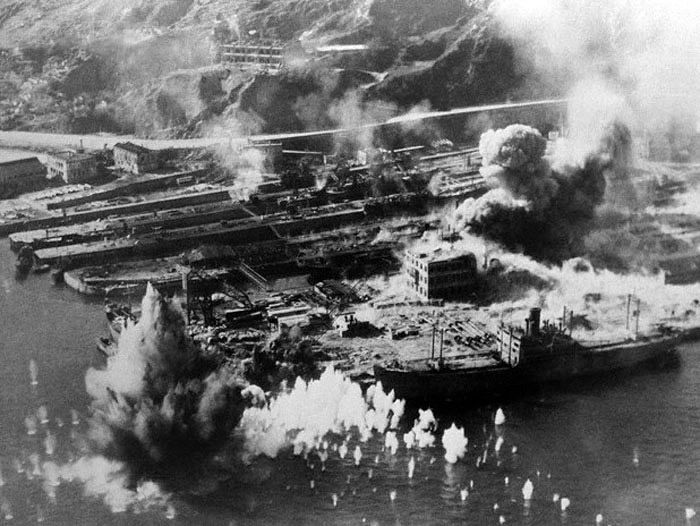

Two Japanese freighters and a tanker are sunk during strikes on Saigon conducted by planes from USS TICONDEROGA CV-14 on 12 January 1945. Note the empennage of the turning aircraft visible at the top of the photo.

-U.S. Navy photo from Brent Jones collection

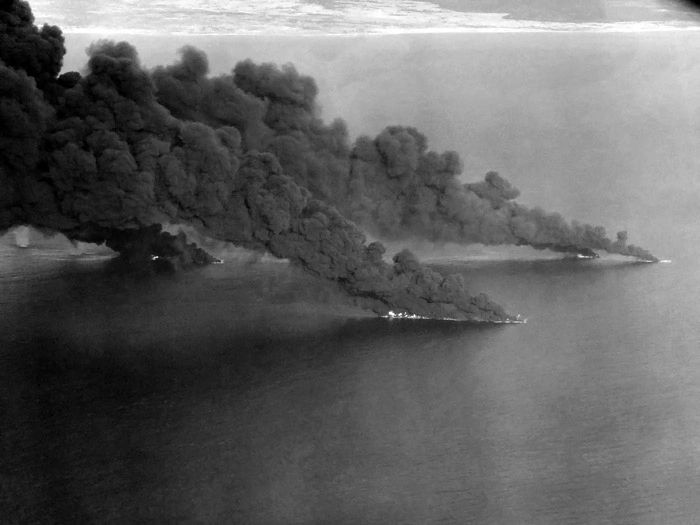

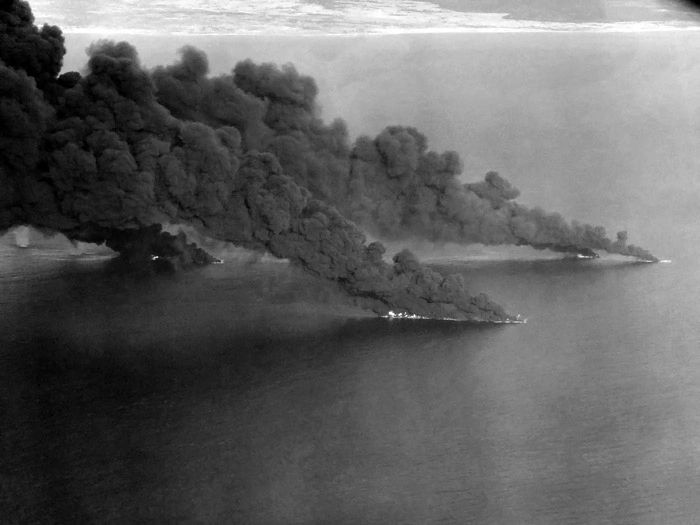

Ships of a Japanese convoy burning heavily off the coast of French Indochina on 12 January 1945.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-301331

A TBM Avenger marked to LEXINGTON CV-16 over the burning Japanese convoy off French Indochina on 12 January 1945.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-301335

Samuel Eliot Morison later wrote:

Task Force 38 planes sank 44 ships totaling about 132,700 tons. Of these, 15 ships... were combatant vessels of the Japanese Navy and 29 ships... belonged to the merchant marine. An even dozen of the sunk Marus were oil tankers. Admiral Halsey did not exaggerate in calling this "one of the heaviest blows to Japanese shipping of any day of the war," and stating that "Japanese supply routes from Singapore, Malaya, Burma, and the Dutch East Indies were severed, at least temporarily."

At 1931, exactly twelve hours after airstrikes were launched, Task Force 38 steamed away from Indochina for a refueling rendezvous with the Logistic Support Group. The U.S. Navy later discovered the true location of the elusive Japanese capital ships. They had been moved much further south to safe anchorage at Lingga Roads, Malaya.

Heavy seas and rain on the morning of 13 January 1945. USS LEXINGTON CV-16 attempts to fuel from ATASCOSA AO-66 while a destroyer takes a heavy roll to starboard.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-299869

13 January 1945

Weather conditions again deteriorated as the task force steamed on a northeasterly course. The high-speed departure from the Indochina coast had served two purposes--to prevent an enemy search and to outrun an approaching typhoon. As the seas rose throughout the morning, fueling proved to be impossible. Many ships parted lines while attempting to pass across fueling hoses.

In an image often incorrectly attributed to Typhoon Cobra, a SUMNER-class destroyer plunges in a trough in the South China Sea on 13 January 1945. This image was taken from NEW JERSEY BB-62.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-470284

ASTORIA had developed a reputation for sound execution in refueling operations. Admiral Halsey singled her out to make an attempt and demonstrate conclusively whether fueling was possible or not.

Bringing a fueling line over from NANTAHALA AO-60 to ASTORIA CL-90 on 13 January 1945.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Moments later, the forward lead line from NANTAHALA to ASTORIA is pulled apart by heavy seas. The fueling effort was subsequently aborted.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Heavy damage to NANTAHALA's stern from a nighttime collision with GUADALUPE AO-32 while transiting Bashi Channel. Both ships were kept in service for South China Sea operations because they were so badly needed. Note the 5" mount propped in place by wooden supports.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

When ASTORIA failed to fuel, Halsey decided to postpone fueling operations until the next day.

With fueling operations postponed, the Logistic Support Group moves away from the fast carriers.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

For the crew of USS ASTORIA, what happened next was the most memorable event from the South China Sea incursion. The ship's forward 20mm battery was not secured, and it began sluing wildly as the ship pitched and rolled. Captain Gerard T. Armitage led several of his men forward to secure the guns.

The two 20mm mounts were situated far forward on the ship's bow. Armitage and his men made their way across the forecastle in treacherous conditions--whipping wind and lashing seas on a slippery deck. They reached the forward battery and managed to secure one of the loose guns. But as they turned their attention to the other gun, the ship dipped into a trough in the high seas. The bow plunged below the surface and the Marines were caught between exposed metal and crashing water.

Two men were battered by the loose 20mm mount. Captain Armitage was lifted off the deck by the surging water and swept clear of the ship. When ASTORIA's bow resurfaced, the Marine Captain was gone.

The bow of USS WILKES-BARRE CL-103 plunges below the surface on 13 January 1945. A similar plunge by twin sister ASTORIA took Marine Captain Gerard T. Armitage overboard.

-U.S. Navy photo courtesy of Robert Brintnall

USMC Captain Gerard Armitage in the water off ASTORIA's port beam on 13 January 1945. Herman Schnipper took this photograph seconds after Armitage was washed overboard.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

The formation was moving at a steady clip through heavy seas; turning to retrieve their lost officer was not a possibility for ASTORIA. The report of "man overboard" was signaled back.

Armitage was wearing a kapok life jacket. The Marine Captain crested mountainous waves and disappeared in troughs, falling further and further behind his ship as the formation passed. The responsibility for a rescue attempt eventually fell upon one of the formation's destroyers, USS HALSEY POWELL DD-686.

HALSEY POWELL was on the perimeter of the task force, miles behind ASTORIA. When she maneuvered to attempt the rescue, she was the only ship able to do so. Her crew fought the same treacherous seas that had swept Armitage from his ship. They eventually managed to get a line to him and reel him in, pulling Armitage aboard and ending a very harrowing experience for the soaked Marine officer in the South China Sea.

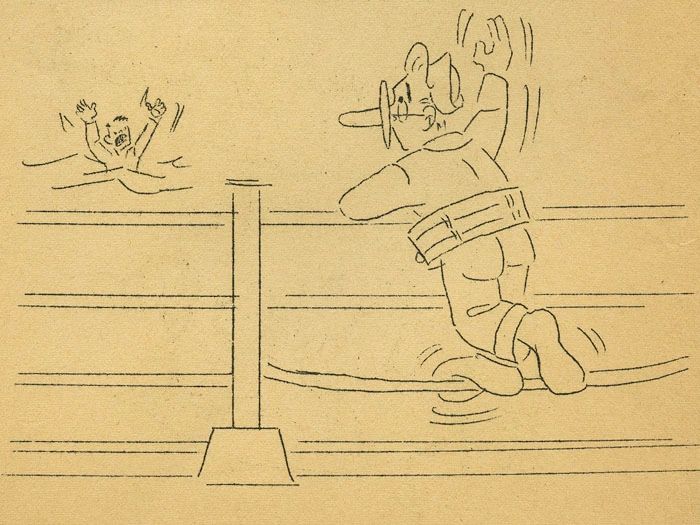

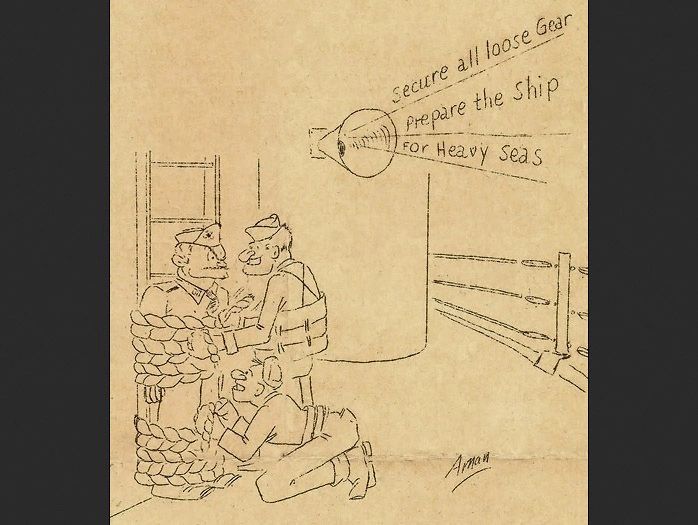

With Armitage safe and sound, Joe Aman drew Joey Fubar waving at his overboard officer in the cartoon from the 14 January 1945 USS ASTORIA Morning Press News.

-Joe Aman cartoon courtesy of Jim Peddie

14 January 1945

Despite more poor weather, the task group managed to refuel the destroyers and bring larger ships to at least 60% capacity. This was enough to continue operations.

USS LEXINGTON CV-16 fuels from an oiler in the South China Sea circa 14 January 1945.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-431080

Sailors and Marines crowd the decks of ASTORIA to watch the destroyer HALSEY POWELL come alongside to return Marine Captain Armitage to the ship on 14 January 1945.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

As the task force refueled, HALSEY POWELL came up alongside ASTORIA. The destroyer demanded the standard U.S. Navy ransom for recovery of an overboard man; Captain Armitage would be returned to his ship in exchange for twenty-five gallons of ice cream from ASTORIA's galley.

HALSEY POWELL DD-686 takes position off the starboard beam of ASTORIA on 14 January 1945.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Captain Armitage is received on the fantail of ASTORIA from HALSEY POWELL on 14 January 1945.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

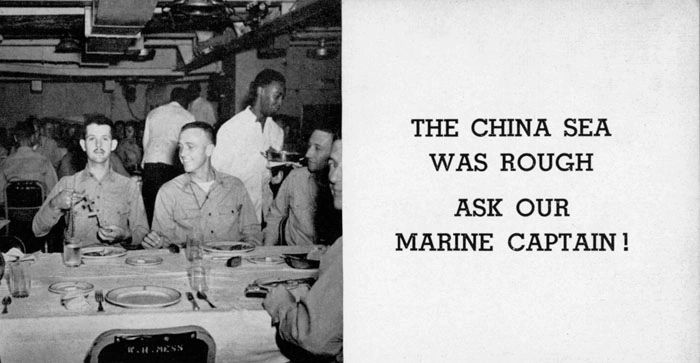

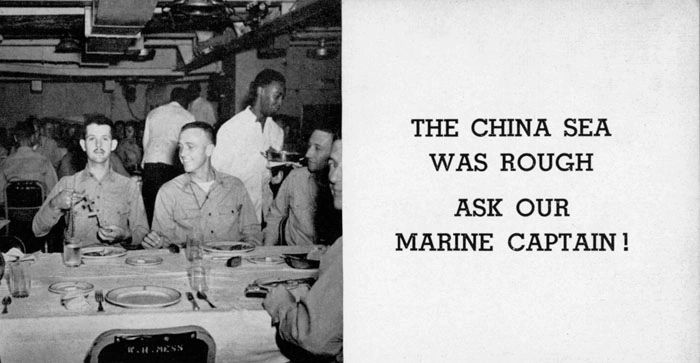

A cryptic entry in the Mighty Ninety cruise book addresses Captain Armitage's adventure. He is holding his "Extinguished Service Cross" in this photo taken in the officers' wardroom mess.

-photo taken by Herman Schnipper (reproduced from Mighty Ninety Cruise Book)

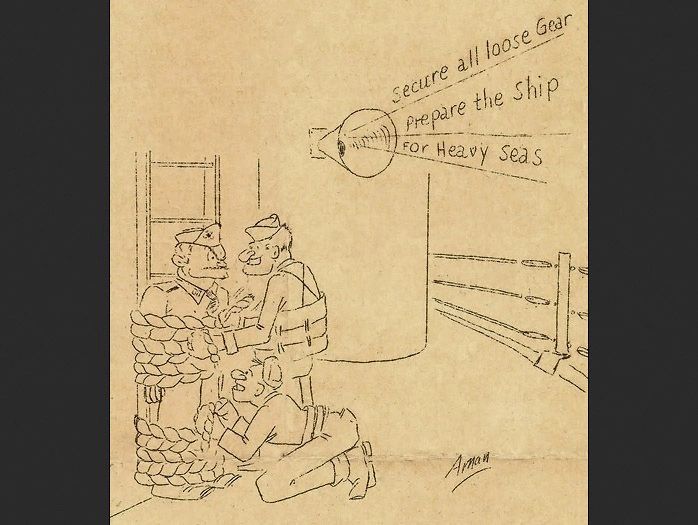

The 15 January 1945 Morning Press News again covered the Armitage adventure in the South China Sea, showing the Marine Captain "secured" for heavy seas with the rest of the "loose gear."

-Joe Aman cartoon courtesy of Jim Peddie

15 January 1945

Halsey was given the green light to conduct further strikes in the direction of Hong Kong. Along the way he intended to continue the search for capital ships of the Japanese Combined Fleet. Weather remained terrible as the Fast Carrier Task Force steamed north. In spite of adverse conditions, the task force launched planes.

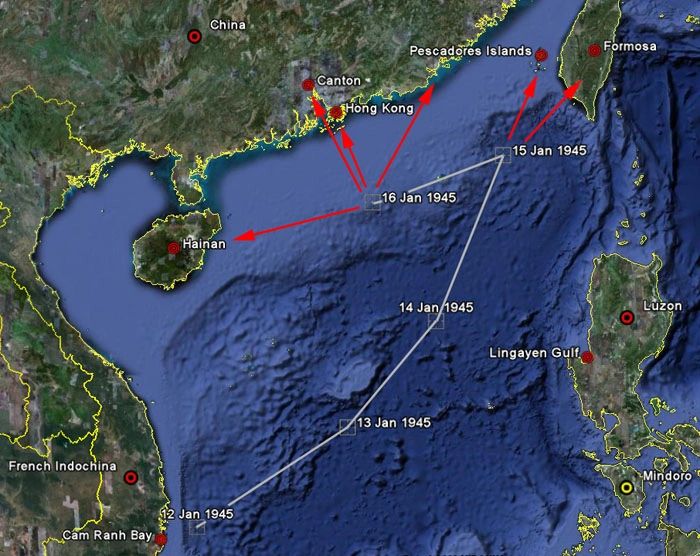

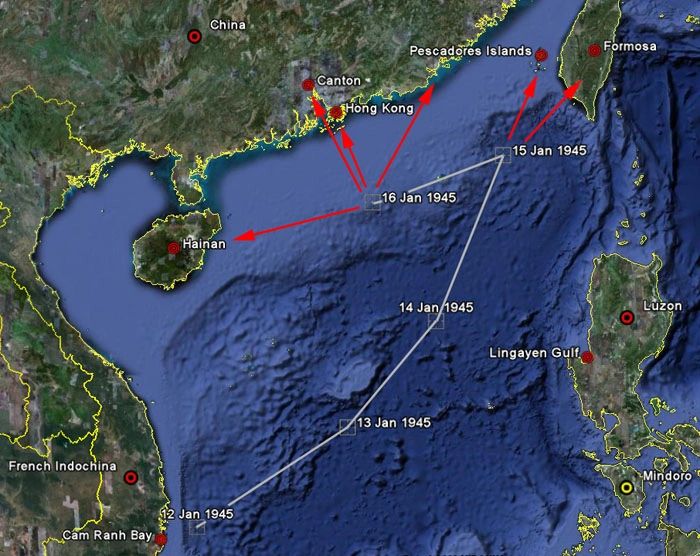

Track chart of USS ASTORIA as Task Force 38 steams away from French Indochina, refuels, and conducts strikes against Formosa and the Chinese coast.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

A Marine F4U Corsair from USS ESSEX lands on the deck of USS HANCOCK circa 15 January 1945. The heavy weather and similarity in deck markings (9 vs. 19) possibly caused mistaken identity.

This was the first Corsair ever to land aboard HANCOCK.

-CPU-13 photo in NARA record group 80-G-259029

F6F Hellcats line up behind the ESSEX Corsair on the HANCOCK flight deck later the same day as they prepare to launch. In contrast to the ESSEX Air Group 4 tail marking, the distinctive horseshoe painted on USS HANCOCK planes is visible on the tail of the first Hellcat.

-Jerome Zerbe photo in Brent Jones collection

16 January 1945

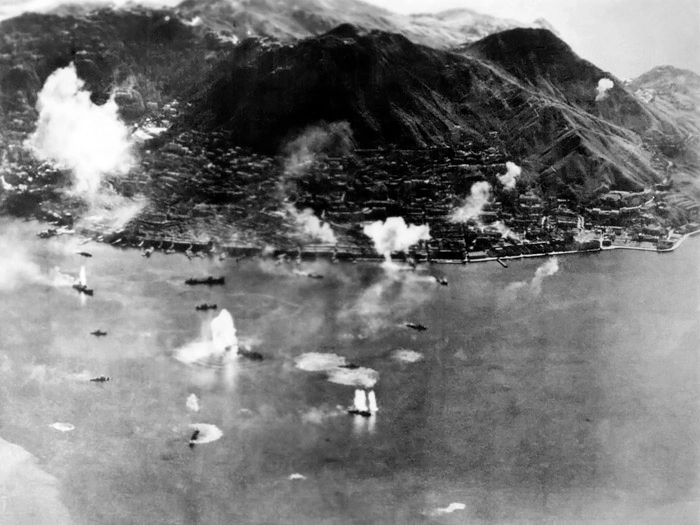

Air strikes launched in the early morning. The focus for the day's attacks was Hong Kong with ancillary raids conducted against Hainan and Canton. Weather was again a factor, and unexpectedly heavy antiaircraft fire also took its toll.

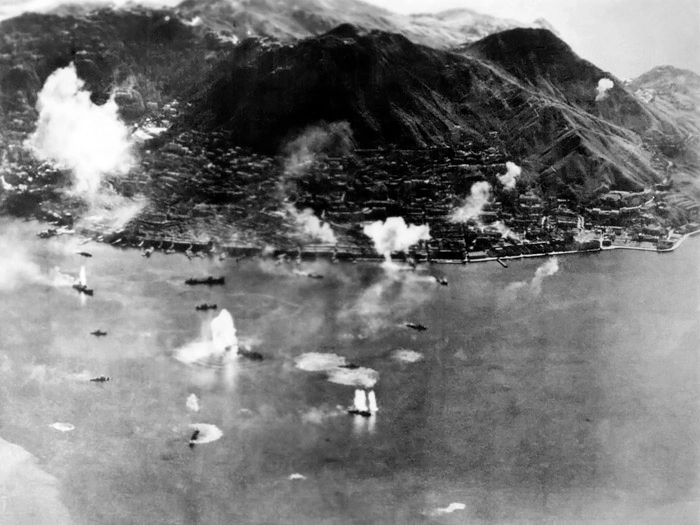

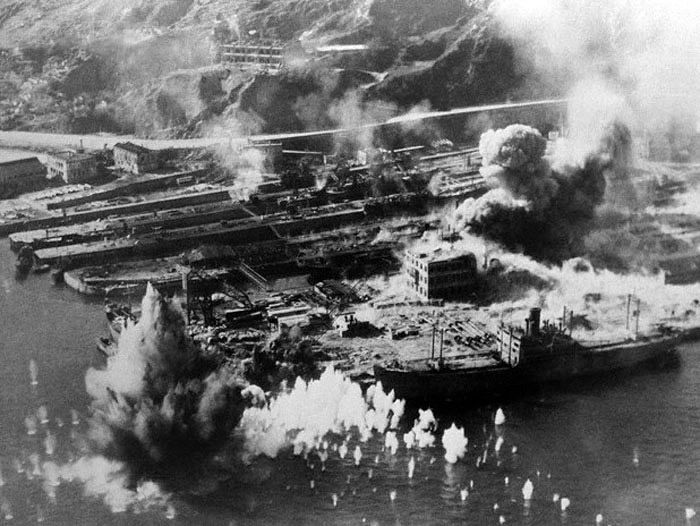

Above and below: Carrier planes strike Japanese shipping in Hong Kong harbor on 16 January 1945.

-U.S. Navy photo in Brent Jones collection

-U.S. Navy photo in Brent Jones collection

-U.S. Navy photo in Brent Jones collection

Overall the results of the day's raids were disappointing. One freighter and one tanker were confirmed sunk with four more ships heavily damaged. Only 13 enemy planes were destroyed, while the fast carriers lost 49 total, many of which fell victim to heavy antiaircraft fire.

Once again, the Japanese Combined Fleet was nowhere to be found. Following the day's raids, Radio Tokyo announced the presence of the Fast Carrier Task Force in the South China Sea. Tokyo Rose reportedly stated, "we don't know how you got in, but how the hell are you going to get out?"

Task Force 38 raids Japanese shipping in the South China Sea

Task Group 38.2 refuels in the South China Sea on 11 January 1945. USS THE SULLIVANS DD-537 and ASTORIA are taking on fuel underway from opposite sides TALUGA AO-62. Note the shamrock on THE SULLIVANS' forward stack. Halsey's flagship NEW JERSEY BB-62 is in the background at left.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Following the surface actions of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, Admiral Halsey was champing at the bit for an opportunity to finish off ships of the Japanese Combined Fleet. Intelligence suggested that the remaining capital ships that had survived the actions at Leyte Gulf were divided into two sections--one group in the Inland Sea of Japan and the other in the South China Sea. Having missed the opportunity at Leyte, Halsey desperately wanted to engage the remaining Japanese surface threat and finish it off.

In January 1945, logistical requirements of the Luzon invasion made this desire a practical reality. The possibility of Japanese warships in the South China Sea posed a significant threat to the supply lines for Luzon. Airfields along the coast of French Indochina (modern Vietnam) and China were also within striking distance of these supply lines. The timing was ideal for a Task Force 38 incursion into Japanese-controlled waters, both to hunt for surface vessels and to strike other targets of opportunity.

9-10 January 1945

Overnight the ships of the Fast Carrier Task Force made a high-speed run southwest, entering the South China Sea via the Bashi Channel of Luzon Strait. This was the first time since the earliest days of the war that U.S. surface vessels had entered these waters.

At 0500 Air Emergency Stations were called--three Japanese "snoopers" had been picked up on radar. The night CAP fighters from USS INDEPENDENCE intercepted them to engage before they could report the presence of the task force.

11 January 1945

Poor weather conditions had prevented fueling the day before, but the morning of the 11th proved successful. Fueling and supply was complete by noon, and effective CAP ensured that the fleet was not discovered while at their most vulnerable. Mail and fuel oil weren't the only things circulating; scuttlebutt began to fly about what the next day might bring.

Confirmation came soon enough. The target area was Cam Ranh Bay, where capital ships of the Japanese Combined Fleet were believed to be anchored. USS ASTORIA's Task Group 38.2, fortified by cruisers and destroyers from TG38.1, was given the assignment of entering Cam Ranh Bay to bombard the area and destroy these surface vessels.

Following fueling, USS BALTIMORE and BOSTON plus five destroyers joined Task Group 38.2. At 1400 this fortified task group, including the night carriers, detached from the main force and began its run-in toward Cam Ranh Bay.

Admiral Halsey sent a message to his ships:

You know what to do--give them hell--God bless you all. HALSEY.

The grid chart used by USS ASTORIA CL-90 in preparation for the Cam Ranh Bay fire mission. The ship was to fire over Tagne Island (lower right) into the bay while her floatplanes spotted her fire.

-courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Track chart of USS ASTORIA as Task Force 38 moves through Bashi Channel between Luzon and Formosa into the South China Sea. After refueling on 11 January, the fortified Task Group 38.2 moved in toward Cam Ranh Bay. The arrows indicate air strikes conducted against Saigon, Cam Ranh, and the coast of French Indochina.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

12 January 1945

At 0300 the night carriers took the lead in the attack on Cam Ranh Bay. Eight two-plane search teams of TBM Avenger bombers launched from ENTERPRISE and INDEPENDENCE.

From Edward Stafford's The Big E:

The blacked-out TBMs fanned out over the [Indochina] coast from a hundred miles to seaward like the fingers of an exploring hand, peering through the night with radar, laying naked suspicious areas with the harsh brilliance of parachute flares, occasionally scorching a rocket or two into likely targets. And behind the probing fingers, the heavy fist of the day carriers was cocked and ready.

At 0731, as the surface strike unit approached Cam Ranh, aircraft were launched from carriers across all task groups. The Avengers launched from the night carriers had provided precise information on locations of Japanese targets, and strikes were dispatched accordingly.

No heavy ships had been sighted. The Japanese Combined Fleet was not in Cam Ranh Bay, nor anywhere else that had been scouted. Frustrated, Halsey ordered the surface strike unit to turn back and the task groups were reconstituted. The focus for the day turned to making the most of the aerial raids taking place against smaller Japanese surface vessels, merchant shipping, and port facilities.

Two Japanese freighters and a tanker are sunk during strikes on Saigon conducted by planes from USS TICONDEROGA CV-14 on 12 January 1945. Note the empennage of the turning aircraft visible at the top of the photo.

-U.S. Navy photo from Brent Jones collection

Ships of a Japanese convoy burning heavily off the coast of French Indochina on 12 January 1945.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-301331

A TBM Avenger marked to LEXINGTON CV-16 over the burning Japanese convoy off French Indochina on 12 January 1945.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-301335

Samuel Eliot Morison later wrote:

Task Force 38 planes sank 44 ships totaling about 132,700 tons. Of these, 15 ships... were combatant vessels of the Japanese Navy and 29 ships... belonged to the merchant marine. An even dozen of the sunk Marus were oil tankers. Admiral Halsey did not exaggerate in calling this "one of the heaviest blows to Japanese shipping of any day of the war," and stating that "Japanese supply routes from Singapore, Malaya, Burma, and the Dutch East Indies were severed, at least temporarily."

At 1931, exactly twelve hours after airstrikes were launched, Task Force 38 steamed away from Indochina for a refueling rendezvous with the Logistic Support Group. The U.S. Navy later discovered the true location of the elusive Japanese capital ships. They had been moved much further south to safe anchorage at Lingga Roads, Malaya.

Heavy seas and rain on the morning of 13 January 1945. USS LEXINGTON CV-16 attempts to fuel from ATASCOSA AO-66 while a destroyer takes a heavy roll to starboard.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-299869

13 January 1945

Weather conditions again deteriorated as the task force steamed on a northeasterly course. The high-speed departure from the Indochina coast had served two purposes--to prevent an enemy search and to outrun an approaching typhoon. As the seas rose throughout the morning, fueling proved to be impossible. Many ships parted lines while attempting to pass across fueling hoses.

In an image often incorrectly attributed to Typhoon Cobra, a SUMNER-class destroyer plunges in a trough in the South China Sea on 13 January 1945. This image was taken from NEW JERSEY BB-62.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-470284

ASTORIA had developed a reputation for sound execution in refueling operations. Admiral Halsey singled her out to make an attempt and demonstrate conclusively whether fueling was possible or not.

Bringing a fueling line over from NANTAHALA AO-60 to ASTORIA CL-90 on 13 January 1945.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Moments later, the forward lead line from NANTAHALA to ASTORIA is pulled apart by heavy seas. The fueling effort was subsequently aborted.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Heavy damage to NANTAHALA's stern from a nighttime collision with GUADALUPE AO-32 while transiting Bashi Channel. Both ships were kept in service for South China Sea operations because they were so badly needed. Note the 5" mount propped in place by wooden supports.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

When ASTORIA failed to fuel, Halsey decided to postpone fueling operations until the next day.

With fueling operations postponed, the Logistic Support Group moves away from the fast carriers.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

For the crew of USS ASTORIA, what happened next was the most memorable event from the South China Sea incursion. The ship's forward 20mm battery was not secured, and it began sluing wildly as the ship pitched and rolled. Captain Gerard T. Armitage led several of his men forward to secure the guns.

The two 20mm mounts were situated far forward on the ship's bow. Armitage and his men made their way across the forecastle in treacherous conditions--whipping wind and lashing seas on a slippery deck. They reached the forward battery and managed to secure one of the loose guns. But as they turned their attention to the other gun, the ship dipped into a trough in the high seas. The bow plunged below the surface and the Marines were caught between exposed metal and crashing water.

Two men were battered by the loose 20mm mount. Captain Armitage was lifted off the deck by the surging water and swept clear of the ship. When ASTORIA's bow resurfaced, the Marine Captain was gone.

The bow of USS WILKES-BARRE CL-103 plunges below the surface on 13 January 1945. A similar plunge by twin sister ASTORIA took Marine Captain Gerard T. Armitage overboard.

-U.S. Navy photo courtesy of Robert Brintnall

USMC Captain Gerard Armitage in the water off ASTORIA's port beam on 13 January 1945. Herman Schnipper took this photograph seconds after Armitage was washed overboard.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

The formation was moving at a steady clip through heavy seas; turning to retrieve their lost officer was not a possibility for ASTORIA. The report of "man overboard" was signaled back.

Armitage was wearing a kapok life jacket. The Marine Captain crested mountainous waves and disappeared in troughs, falling further and further behind his ship as the formation passed. The responsibility for a rescue attempt eventually fell upon one of the formation's destroyers, USS HALSEY POWELL DD-686.

HALSEY POWELL was on the perimeter of the task force, miles behind ASTORIA. When she maneuvered to attempt the rescue, she was the only ship able to do so. Her crew fought the same treacherous seas that had swept Armitage from his ship. They eventually managed to get a line to him and reel him in, pulling Armitage aboard and ending a very harrowing experience for the soaked Marine officer in the South China Sea.

With Armitage safe and sound, Joe Aman drew Joey Fubar waving at his overboard officer in the cartoon from the 14 January 1945 USS ASTORIA Morning Press News.

-Joe Aman cartoon courtesy of Jim Peddie

14 January 1945

Despite more poor weather, the task group managed to refuel the destroyers and bring larger ships to at least 60% capacity. This was enough to continue operations.

USS LEXINGTON CV-16 fuels from an oiler in the South China Sea circa 14 January 1945.

-U.S. Navy photo in NARA record group 80-G-431080

Sailors and Marines crowd the decks of ASTORIA to watch the destroyer HALSEY POWELL come alongside to return Marine Captain Armitage to the ship on 14 January 1945.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

As the task force refueled, HALSEY POWELL came up alongside ASTORIA. The destroyer demanded the standard U.S. Navy ransom for recovery of an overboard man; Captain Armitage would be returned to his ship in exchange for twenty-five gallons of ice cream from ASTORIA's galley.

HALSEY POWELL DD-686 takes position off the starboard beam of ASTORIA on 14 January 1945.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

Captain Armitage is received on the fantail of ASTORIA from HALSEY POWELL on 14 January 1945.

-photo taken by and courtesy of Herman Schnipper

A cryptic entry in the Mighty Ninety cruise book addresses Captain Armitage's adventure. He is holding his "Extinguished Service Cross" in this photo taken in the officers' wardroom mess.

-photo taken by Herman Schnipper (reproduced from Mighty Ninety Cruise Book)

The 15 January 1945 Morning Press News again covered the Armitage adventure in the South China Sea, showing the Marine Captain "secured" for heavy seas with the rest of the "loose gear."

-Joe Aman cartoon courtesy of Jim Peddie

15 January 1945

Halsey was given the green light to conduct further strikes in the direction of Hong Kong. Along the way he intended to continue the search for capital ships of the Japanese Combined Fleet. Weather remained terrible as the Fast Carrier Task Force steamed north. In spite of adverse conditions, the task force launched planes.

Track chart of USS ASTORIA as Task Force 38 steams away from French Indochina, refuels, and conducts strikes against Formosa and the Chinese coast.

-manipulated from Google Earth imagery

A Marine F4U Corsair from USS ESSEX lands on the deck of USS HANCOCK circa 15 January 1945. The heavy weather and similarity in deck markings (9 vs. 19) possibly caused mistaken identity.

This was the first Corsair ever to land aboard HANCOCK.

-CPU-13 photo in NARA record group 80-G-259029

F6F Hellcats line up behind the ESSEX Corsair on the HANCOCK flight deck later the same day as they prepare to launch. In contrast to the ESSEX Air Group 4 tail marking, the distinctive horseshoe painted on USS HANCOCK planes is visible on the tail of the first Hellcat.

-Jerome Zerbe photo in Brent Jones collection

16 January 1945

Air strikes launched in the early morning. The focus for the day's attacks was Hong Kong with ancillary raids conducted against Hainan and Canton. Weather was again a factor, and unexpectedly heavy antiaircraft fire also took its toll.

Above and below: Carrier planes strike Japanese shipping in Hong Kong harbor on 16 January 1945.

-U.S. Navy photo in Brent Jones collection

-U.S. Navy photo in Brent Jones collection

-U.S. Navy photo in Brent Jones collection

Overall the results of the day's raids were disappointing. One freighter and one tanker were confirmed sunk with four more ships heavily damaged. Only 13 enemy planes were destroyed, while the fast carriers lost 49 total, many of which fell victim to heavy antiaircraft fire.

Once again, the Japanese Combined Fleet was nowhere to be found. Following the day's raids, Radio Tokyo announced the presence of the Fast Carrier Task Force in the South China Sea. Tokyo Rose reportedly stated, "we don't know how you got in, but how the hell are you going to get out?"

Continue to CHAPTER 14: OPERATION GRATITUDE part 2

CLICK PHOTOS TO ADVANCE TO NEXT CHAPTER

Sources:

Aman, Joseph. Joey Fubar's Cavalcade of Humor. Printed aboard USS ASTORIA CL-90, 1945.

Dyer, George C., Vice Admiral USN (Ret.) Personal interviews conducted by John T. Mason, Jr.

Annapolis, MD: 1970

http://commons.Wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Wikimedia Commons image database.

http://earth.Google.com/ Google Earth.

Jones, Brent. Private photo and document collection.

MIGHTY NINETY: USS ASTORIA CL-90 cruise book. 1946.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in WWII Vol. XIII: The Liberation of the Philippines. Boston: Little, Brown and Company Inc., 1959.

Peddie, Jim. Private document collection.

Schnipper, Herman. Private photo and document collection.

Stafford, Edward P. The Big E. New York, NY: Random House, Inc., 1962.

www.usshancockcv19.com USS HANCOCK CV-19 Association website.